- Home

- Blakey, Moonyeen

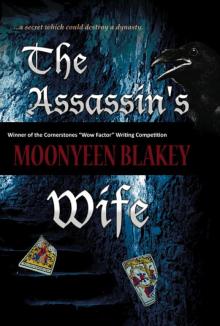

The Assassin's Wife

The Assassin's Wife Read online

The Assassin’s Wife - Copyright © 2012 by Moonyeen Cooper

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced by any means without the written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotation embodied in critical articles and reviews.

ISBN-13: 978-1-61179-218-8 (paperback)

978-1-61

179-219-5 (e-book)

BISAC Subject Headings:

FIC014000 FICTION / Historical

FIC024000 FICTION / Occult & Supernatural

FIC037000 FICTION / Political

Cover design by Christine Horner

Address all correspondence to:

Fireship Press, LLC

P.O. Box 68412

Tucson, AZ 85737

Or visit our website at:

www.FireshipPress.com

1.0e

Table of Contents

Dedications

Acknowledgments

Prologue

Part One: Stanwode, Northamptonshire, 1460

Part Two: London, late 1460

Part Three: Norwich, 1463

Part Four: London, 1464

Part Five: Middleham, 1471

Part Six: London 1478

Part Seven: Middleham, 1478

Part Eight: London, 1484

About the Author

For my parents,

Frederick George and Muriel (nee Higginson) Blakey,

who never stopped believing in me.

And for Eddie, a rock and a haven.

What would I do without you?

Acknowledgments

A big thank you to the stalwarts of Yarburgh Writers’ Group who endured all the rewrites of The Assassin’s Wife — especially Tom Beardsley, Sandra Bensley, Lesley Dover, Michelle Elliot, Dave Evardson, Kris Gleeson, Millie Gough, Chris Green, Louise Law, Sylvia Lover, Frank Payton and Jen Ward — whose constructive criticism proved invaluable. And thanks to former Arts Development Officer for Lincolnshire, author Paul Sutherland, Editor of Dreamcatcher, who continues to monitor our progress.

Special thanks to authors Sally Spedding and Karen Maitland who have not only lent a sympathetic ear, but offered generous amounts of practical advice. Their continued support and enthusiasm keeps me buoyant!

Thanks, too, to Cleethorpes Library Staff — particularly Jane Coward — and to the Cleethorpes Library Readers’ Group, to Michelle Elliot for her photographs, to Edmund Harness for rescuing me from the many and devious schemes of computers, to Kris Gleeson, whose wisdom and friendship remains inspiring and unfailing, and to my patient neighbour, Rhona Emsley, a shoulder to cry on and a tower of strength in matters practical.

And fond memories of absent friends who also played a part in this novel reaching fruition: Joan Hackney, Barbara Harness, David Mordaunt and Heather Sparnon.

Last but not least, my thanks to the staff of Fireship Press, especially my erudite, energetic and patient editor, Jessica Knauss.

Prologue

“It will be a cruel death.”

The smooth voice brushes my ear, soft as a caress.

The wood is too green. Only thin trails and wisps of smoke trickle along these damp limbs wrenched from the living tree, spiralling among the intricately-woven basket-work. Caged, the girl stands bound and mute, her head lifted as if to sniff the acrid scent that rises, teasing and prickling the nostrils. Around her the spectators snatch a breath, thrust against each other, tensed for the entertainment that begins now.

Tiny shoots of flame race across the dry sticks some charitable wretch has thrown, licking and sucking at moisture until the black stench becomes a storm-cloud. We are engulfed. Complaining, the worshippers jostle for air and blink away tears.

“I can’t see!” The voice is querulous.

The crowd surges forward, open-mouthed, panting with excitement. Bodies press closer as I struggle to escape the crush, the reek of tainted breath, but stout hands hold me. I’m grateful for the mask of fog, though my ears still catch the crackle and the hiss, the roar of burning wood. When the smoke clears, the flames are ragged, gaudy butterflies that leap and plunge, fluttering into ash. The sacrificial figure twists and capers among them, begins to sing. It is an anthem to pain. We gasp and clutch, rank with sweat, straining towards a terrible fulfilment.

“The fire is a demanding lover,” insists the voice at my ear. “See how closely it embraces.”

I shrink from the heat but the guards’ grip is merciless. The song has become a howl, the dance a frenzy.

“Nerys! Nerys!” My voice is hoarse, useless. I am shamed.

Through the gamey smell of roasting and the stinking smoke, I watch her features begin to melt and drip like candle-wax. The black strands of her hair ignite and flare like sun-rays, copper-bright around her head, in brief glory.

Sweating, panting, we moan together, shudder and roll upon a spasm of pleasure that peters out into a mere sigh.

Spent and hushed, the crowd separates. The spell is broken.

“You see now what it is to burn a witch.” The voice is hard, implacable.

I close my eyes. Tears ooze between my lashes but it is fear, not grief that feeds them.

“I don’t want to see,” I say. “I don’t want to see.”

Chapter One

“Liar!”

“But I did see him! I did!”

Johanna’s fist struck me hard across the mouth, splitting my lip.

Sensing blood, boys and girls spilled out of trees and across wasteland. Their voices soared, excitable, unstable. Soon a jostling circle harried us with jeers and shouts.

“Liar! Liar! Liar!”

Johanna seized me by the hair and forced me to my knees. Fleetingly I glimpsed the shifting web of faces hanging over me—mouths spitting spite. And all the while the noise grew louder like the roar of kindling catching fire.

Dragging, shoving, stumbling, they brought me to the pond. Sunlight dappled its lazy, scummy surface. Its poisonous reek tainted the breeze.

Fingers still embedded in my hair, Johanna pushed my face deep into the water. The shock of it was like a bite. No time to scream. No time to breathe. Liquid flooded my mouth and nose.

Wrenched upward for a blessed moment, I snatched at air until she thrust me under. Another rise and gulp, a blast of sound, and then the press, the drag, the pull, the awful, greedy darkness—

“For the love of God!”

I retched among the reeds, noise exploding in my ears.

“Do you want her to drown?” Brother Brian’s voice shook with horror and disbelief.

“She said she’d seen spirits.” Johanna’s harsh voice condemned me.

“She makes up stories. She’s just a little girl.”

“She told me she’d seen my brother walking by the water-mill. But Will’s been dead three months since Easter.”

“She’s after telling you some tale she’s fashioned—”

“Liars should be punished!”

“Yes, but according to their age and by those who understand these matters, not by a mob. Go home now, all of you.”

The kindly priest spoke firmly and the group obeyed, but not without some sullen murmurs.

“Can you walk?” He held out a hand.

I nodded, twisting water from a sodden skirt. Green-stained and stinking, I rose, trailing slime from tangled hair.

He led me along the dusty, winding track to the yew-shadowed church. Inside its cool, dark walls I stood, uncertain, arms clasped about my shoulders. Looking upward, I glimpsed the stone carving of Saint Michael, sword raised high, straddling a crouching demon with curved fangs and scaly tail. Although the grim-faced angel was reputed to protect our village, I felt no reassurance in his stern presence. Gently Brother Bri

an steered me to the little chapel where he kept his vestments. Dripping and shivering, I waited, transfixed by the flames of Hell leaping up the painted walls, appalled by mocking demons wielding pitchforks, their wide mouths full of pointed teeth.

“Dry yourself.” Bundling my ruined shift into a sack, he offered a coarse cloth. “No need to be afraid.” He turned me from the sooty demons to wrap me in a dusty cloak. The reassuring kindness of his pale features comforted and I lifted my eyes in gratitude.

He drew a bench from a pile by the wall where an open press revealed some scrolls, some pots of ink and goose-feather pens. Across a trestle lay scraps of vellum decorated with loops and curls and inky finger-marks. I remembered then he taught the village boys their letters and marvelled at these curious scratchings like bird-feet in the snow.

He followed my gaze.

“The boys are after practising their writing.” A smile curved his mouth. “Sit down.” Plucking a piece of parchment he held it up for my approval. “Master Palmer has talent. He may yet prove a scholar—”

The quiver in his voice signalled me to study his face. A pair of troubled blue eyes met mine and I sensed at once he guarded a secret of his own.

“Now tell me what you saw.” His speech lilted, soft and liquid. After years among us he still spoke like an outsider.

I closed my eyes, conjuring again the ring of chanting, spiteful children, inhaling the ferment of pondweed and recoiling from the slap of water against my skin.

“Why did it upset Johanna Nettleship so much?” Sitting beside me, the hairy fabric of his dark robe brushing my arm, he put a cup of wine into my hand. Dutifully, I tried to swallow, but gagged, spewing a stream of bile and pond water across the flagstones instead.

“No matter.” He stooped to wipe away the mess, crouching beside me, his expression serious. “Was it just a bit of pretending, a bit of making up stories to frighten her? Or were you after seeing shadows on a wall?”

“I saw Will Nettleship as clear as I see you now!” I clenched my fists, and the church rang hollow with my shouts. “I told you before, I don’t see shadows. I don’t make things up. I see real people like the boys in my dreams who’ll be killed if I don’t find them.” Impotent rage shook me. I fixed him with a fierce, unforgiving glare. “I thought you understood. You said you’d help me. Why won’t people listen? Why don’t you believe me?”

“Child, child, I do believe you. You have the Sight,” he answered, his voice so weary, his kindly face so grave, all my hurt and anger ebbed away. For a moment he studied his ink-stained fingers. Then his eyes flicked towards the statue of the Virgin by the little altar beneath the lancet window where a single candle glowed. He crossed himself. “But you must ask Our Lady to shelter you from these dark fancies.”

“Am I a witch then?” I stared at the plaster face and the blue-painted robes, seeing no warmth or comfort in them. Unwelcome, my mother’s face swam into my mind. Her eyes were just as empty.

“No, no.” He touched my arm. “You mustn’t think such things.”

“But I see spirits. My mother says it’s wicked. And her friend, Marion— Mistress Weaver, says—”

The candle spluttered, distracting us.

“What happens to the moth that’s drawn to the candle-flame?” The priest’s eyes focused on the flickering light.

“It gets burned.”

“So we must learn to avoid danger.” He looked at me intently.

“Am I to tell lies then?” I jerked as if stung. “I didn’t think priests were supposed to tell lies.”

I wanted to hurt him as I’d been hurt, but he answered soft and mellow.

“No lies. But you must guard your tongue. Such talk of spirits frightens people and puts your family in danger. Better to keep silent than invite undue attention.”

“I saw a man in the water.”

“What man?”

“In the pond. He floated up towards me. His eyes were open but his face had swollen. Rags of skin were peeling from it.”

“A drowned man?”

“Oh yes, but not from here. A nobleman. He said he’d been murdered.”

The priest pressed a finger to my lips. “You mustn’t speak of this to anyone. I’ll talk to your mother and put her mind at rest. No need for fretting.”

He took me home under the scrutiny of gossip-hungry villagers on the green, smiling away churlish remarks, rebutting them with cheerful greetings and questions of concern about their families. When we reached the tight fist of houses at its farther edge, the Askew girls stepped from their neighbouring cottage to gawk at me and I clasped his hand tighter.

At our makeshift door my mother waited, holding Tom in her arms. Her eyes accused me, needle-sharp, unkind, but she turned a smiling mouth to Brother Brian and stood aside to welcome him into our home.

“Put this on.”

Setting Tom on the floor to play with some little wooden animals my father had carved, she flung a patched shift at me and offered the priest a stool by the hearth.

“I’ll wash your cloak,” she said, brushing away his murmured deprecation. Wrinkling her nose with distaste, she dropped the sack containing my wet shift into a pail. “Take this outside, Nan, and wait until I call you.”

I flashed the priest a glance and caught his smile to comfort me.

“John’ll be home soon, Brother Brian. He’s helping Noll Wright to mend a cart. Will you take some ale?”

My mother’s honeyed words brought fresh bile into my mouth. I dropped the ragged leather flap behind me.

“That’s her.” Rabbit-toothed Elaine Askew dragged her younger sister to stare at me over their straggling hedge. I pretended interest in a wayward hen which had crept into our garden to forage. “She sends ghosts out in the night.”

“Come away!” Her mother’s voice rose shrill with anger. “I told you not to speak to her.”

“I didn’t speak to her. I only told Mattie what Johanna Nettleship says.”

“I don’t want to hear what Johanna Nettleship says—” Her mother left off feeding squawking chickens to hustle the girls away, glowering at me as if I were to blame for their disobedience.

I stuck my tongue out at her retreating back and shooed the startled hen under the hedge to join its outraged sisters, watching them scatter in a clucking flurry of feathers. Glaring a challenge at other impudent watchers, I hurried off to find my father.

“Trouble’s brewing.”

Noll Wright’s voice, gravel dark and deep, drew me to the forge. Half-sprawled on the ground, he and my father struggled to fix a wheel to a cart. Unnoticed, my nose full of the pungent smells of horse and dung, I crept closer.

“It might be better to choose someone with his wits about him.” Noll shook his iron-grey head and grabbed a hammer.

“They’re saying in Brafield the Duke of York has his eye on the crown.” My father stood and stretched with a luxurious groan. “That’s it, Noll, as good as new.” He turned. “Here’s Nan to fetch me to my supper.” His voice held smiles, but something in his eyes warned me he’d already heard about Johanna.

Noll Wright glanced up with a growl of disapproval as I flung my arms about my father. I pressed my face against the soft, faded leather of his jerkin, breathing in the familiar smells of wood-smoke and grease.

“That’s a nasty cut.” He tipped my chin and touched a finger to my bloodied lip. “Suppose you tell me all about it on the way home.”

I gripped his hand and began to whisper my story, shutting out the rest of the world, wallowing in the surety of his love.

“There you are!” My mother snatched me inside, her face a white mask of fury. “Didn’t I tell you to wait until I called you?” She slapped me hard, tears of anger filling her eyes. “I suppose she told you some garbled tale which you believed.” She rounded on my father like a vixen.

“I heard some foolish talk—”

“Talk! The whole village’s gossiping about her. Marion says it’s got as far as Brafield. I

’m frightened, John. It’s not just old folk stories now. She’s nine—old enough to know what she’s saying. Brother Brian had to bring her home—The shame of it! And she still disobeys me—”

Tom whimpered and I crept into a corner while she picked him up and crooned soft words against his cheek. Rigid-backed, she stooped over the hearth stirring the broth for supper.

We ate in silence.

Later as I lay on my pallet, they argued. For the first time in my life, my father’s voice grew thunderous. I rolled myself into a ball to shut out the noise. It was as if a great curdling storm cloud had finally burst. Long after the house quieted, I lay awake, listening to the steady drum of rain upon the thatch. The foundations of my world began to slip and slide.

The flicker of the flame woke him. It was no more than a hiss, like a drop of moisture on hot metal, but the sound jolted him awake. His lids opened just as a broad hand reached out to extinguish the candle and the chamber plunged into darkness.

“There’s someone in the room, Ned.” He pinched the naked flesh beside him. “Are you awake?”

Whispers.

He strained to catch the words, clutched at the prone body beside his, desperate for a protest of complaint, but too afraid to throw back the coverlet or challenge the shadows. He ached for a cherished voice, for a gentle hand on his brow, for the laughter and the pageantry that had once been his. But the isolation and intrigue of this long confinement was blotting out those memories of homage and acclaim.

He held his breath, listened to the waiting silence—heard only the thud of his own heart, a quickening pulse that terrified. The other boy lay warm and still, wrapped in poppy-fed dreams beyond his reach. The doctor had used compassion.

The Assassin's Wife

The Assassin's Wife