- Home

- Blakey, Moonyeen

The Assassin's Wife Page 6

The Assassin's Wife Read online

Page 6

No one listened to me. I lay alone in my bed planning a tearful revenge. If only I could turn time back and avoid that foolish game so that everyone still loved me!

Chapter Ten

In the bleak chill of a winter’s morning Aunt Grace rushed me through the winding streets to the Chepe where the busy market stalls and shops touted their wares. I suppose she was too frightened to defy my uncle, but it seemed as if she couldn’t wait to be rid of me. How I despised her weakness!

On the corner of Bread Street, always warm and fragrant with fresh baking, we stopped at a big shop. Aunt Grace pushed me inside.

“Is this the maid?” The stout woman in the bleached linen apron turned to stare. From the open bake-house door wafted a mouth-watering smell of new bread, and the sight of heaped loaves and pastries on the shelves caught my greedy eyes.

“Aye, this is Nan.”

Aunt Grace nudged me forward like a horse for inspection.

“How would you like to help me in the bake-house?” the woman asked. She regarded me shrewdly. “I could use an extra pair of hands.” Ignoring my sullen silence, she nodded to my aunt. “She can sleep in Philippa’s chamber.”

This news alarmed me. Was I to be a servant now? Who was Philippa?

Still smarting with the injustice of my exile, I feigned indifference. As their punishment, Uncle Will denied my cousins the royal procession, but he sent me away to work. It wasn’t fair. But then a little, niggling doubt sprouted like a weed. Suppose I was to blame for all the things that had happened? Suppose I was a witch? What should I tell Brother Brian when he came to visit?

A dusty young man with a scar on his cheek appeared from the bake-house.

“Take Nan to your father,” Mistress Mercer said. “He’s expecting her.”

The sight of the bake-house immediately brought back the vivid pictures I’d seen for Meg. Motes of flour floated in the air, and a blast of heat as if from a great furnace enveloped me. Out of searing mist appeared Big Hal, Mistress Mercer’s husband, a giant in a straw-coloured jerkin, his face powdered thick and white like a spectre’s. Nodding and smiling, he scraped out crumbs and ashes from the ovens with huge, dust-dried hands, while Harry, the sturdy, brown-haired youth with the kindly face, lifted trays heavy with hot loaves on to a trestle just as I saw in my vision.

Wiping floury hands upon his apron and inky-coloured hose, Harry gave me a friendly wink. “These will be delivered to the rich houses in the city. My father bakes the finest bread in London. No one has a reputation to match his. Mercer’s bread is famous.”

Scorched by the breath of the ovens, I watched Harry’s strong hands kneading and shaping dough. The lad’s cheerful manner put me at ease and I listened hungrily as he confided to me the secrets of Mercer’s famous bread. Though the big man with the powerful shoulders said little, his eyes twinkled with good humour. I felt an immediate desire to earn his approval. Perhaps, Brother Brian was right about things happening for the best. Here, in the heart of the pie shop, I’d learn new skills and meet new people.

But I learned quickly that Mercer’s pie-shop wasn’t just famous for its delicious breads and dainties. It bubbled with juicy morsels of gossip in a city teeming with rumour, and throughout my first week the shop buzzed with talk of a fearful battle in the north in which the Duke of York had been killed.

“They stuck his head on Micklegate Bar in York so he could over-look the city,” a talkative matron said, twitching at her brown hood. She opened her eyes wide in pretended horror. “And his son’s too.”

Astonished, I listened avidly. Had Brother Brian heard this tale? And would he think of me?

In these early days, clever Margaret Mercer made no attempt to win my confidence. She kept me busy and asked no questions. But bit by bit she lured me into the circle of her affection. Though Aunt Grace came to see me often, sometimes bringing a sheepish Sarah with her, I greeted her with grudging courtesy, listening behind the bakery door and gloating when she wept: “ I’d have her back at the house, Margaret, but Will—I treated her like one of my own and she was just beginning to settle when—”

“There, there,” Margaret Mercer would say, “She’ll come round in time. She’s doing well, and Hal enjoys her company—and as for Harry—She’s an uncommon child. Just leave her be a while. Let her grow used to us. It’s not been easy for her.”

Clever Margaret Mercer—I think she knew I listened but I didn’t care. I was still a novice in the art of dissembling. No one had considered my feelings before. I’d not come here willingly, but now I determined to stay. Harry had won my heart.

It was easy to love the homely youth who treated me with simple kindness. He entertained me with stories about the city and in his leisure time let me watch him carving animals from bits of wood. The little, knock-kneed horse he gave me became my greatest treasure. I hung on his words and followed after him, longing to confide my secrets. But mindful of the priest’s solemn counsel to ask the Virgin to take away my “dark fancies,” I said my prayers and struggled on alone.

Harry first took me through the warren of streets in the Chepe and taught me about the city. Gradually the sights and sounds grew familiar. Delivering baskets of succulent, golden pies, and honey-glazed pastries allowed me opportunities to see the market traders at their stalls, and explore the lanes bustling with shops. The tangy stink of the fishmongers, the pungent butcher’s stall, and the aromatic scent of leather from the shoe-maker’s filled my nostrils. I revelled in the sharp odour of resin from the carpenter’s shop and learned to distinguish the mingled smells of beeswax, honey and wine. By degrees I grew proud to belong to this family of tradesmen. I loved to watch the milling people. Peddlers, hawkers, pilgrims, ragged vagrants begging for alms, raucous apprentice boys with impudent faces, blousy women in draggled skirts accosting burghers, painted players, cut-purses and jugglers formed only a part of the throng which filled my daily life with colour and noise.

On one of these occasions I met Maud Attemore, the cutler’s wife, who kept the shop in Forster Lane.

“You’ve a new helper, Harry?”

The woman’s handsome, weather-roughened face smiled down at me. Harry grinned back as if sharing a joke.

“This is Nan, Mistress Attemore. She’s learning her way round the city so she can make deliveries on her own soon.”

“She’s a lucky maid then.” Mistress Attemore, a striking figure in a garnet gown with mole-hued sleeves, picked coins from a worn leather purse. “She’s got the best of guides.” She winked as she counted the money into Harry’s dusty palm. “What do you think of London, Nan?”

The bright expression encouraged confidence but I wouldn’t answer.

“Shy, is she?” Mistress Attemore darted a bold glance at Harry. “She’s a bonny, little thing. Lovely grey eyes—just like wood-smoke.”

“She’s from the country,” said Harry. He dropped the pennies into a cloth bag and tied it fast. “It’s a bit strange to her here, but she’s learning fast. Shall I put these pies on the shelf?”

“Aye, there’s a good man.” She craned her neck to watch people passing in the street—a habit I got to know well, for Maud Attemore never missed a thing.

“Well, look at that!” She smiled with satisfaction. “See that fine lady just outside, Nan –the one in the rose-coloured gown?”

She turned me by the shoulder and pointed to a stately figure in velvet standing by a jeweller’s shop across the way.

I nodded, holding my breath with wonder. The woman stood straight and slender, her hair hidden beneath gold nets decorated with pearls on each side of her face, exposing the white sweep of her brow and finely arched eyebrows. On the top of her head sat a fantastical heart-shaped cap draped with a gauzy veil in palest rose. The gown itself hung in shimmering folds, the wide sleeves cut into points that almost swept the ground. Below the skirt I glimpsed purple leather shoes with high wooden soles and heels.

“One of the queen’s ladies.” Maud laughed at my a

mazement. “See the two men-servants in blue livery? No noblewoman goes out without someone to protect her. There’s always something going on in the city, Nan. You’ll soon learn to love it as we do.”

Harry lurked at my elbow, eager to be gone.

“Wait,” said Mistress Attemore, disappearing into the shop.

She was back in a moment and holding a reddish ball under my nose.

“Take it,” she said, with a wink at Harry. “A pomegranate. A welcome gift.”

“What is it?” I trotted after Harry like an obedient puppy.

His laughter warmed me.

“Maud Attemore’s the biggest gossip in the city,” he said. “If you want to know anything, just ask her.” He took the pomegranate. “And this is a fruit.” He tore back the thin, leathery skin to reveal the ruby flesh of the seeds.

“Like jewels,” I said, dazzled by this new wonder.

“Sweet,” said Harry, “all the way from Spain.”

We shared Maud Attemore’s treasure as we finished the rounds, and I raced Harry back to the shop.

Chapter Eleven

My life took a new turn. Days flew by so swiftly, I’d little time to brood. At night I dropped into a heavy, dreamless sleep from complete exhaustion.

We rose early, for the bread must be in the ovens before dawn streaked the sky, and I went out with deliveries while it was still warm. The day’s business so occupied me I ceased to think of the visions, and if spirits roamed among the throng in the streets I didn’t recognise them. Instead I glimpsed the wealthy ladies carried upon litters, goggled at jewel-encrusted gowns and elaborate head-dresses, and admired the noblemen astride brightly caparisoned horses.

Harry made me a regular visitor to my uncle’s house, sending me with tokens for Meg. Both families approved this burgeoning love affair, and with three daughters to be wed, poor Uncle Will’s mind buzzed over the next months. Scarcely had Judith celebrated her marriage in far off Lincolnshire, than Meg was planning hers.

Philippa and I chattered of it incessantly as we lay in the comfortable seclusion of our little chamber high above the bakery.

Philippa turned out to be a handsome, bold-eyed wench of fourteen or so, who helped in the shop and sometimes took baskets of bread and pies to special patrons. She treated me like a younger sister and delighted in teaching me all the feminine arts. Her knowledge of the latest fashions and city scandals soon won my admiration. I longed to have her easy manner with the customers and secretly coveted the golden hair that tumbled down her back like liquid gold.

“Why do you always braid it?” she asked one night, watching me brushing my own hair before bed. “You should wear it loose.” Taking the brush, she made long, sweeping strokes through the curling mass which hung to my waist, humming with satisfaction as it crackled under her fingers. “See how thick it is!”

“But it’s dark,” I said with a dissatisfied pout, “not fashionable. I wish it were fair like yours.”

She shook her golden mane, laughing as she ran her hands through the silky locks. “But mine’s nowhere near as thick as yours. Yours has such a sheen. See how it gleams red under the light. It’s a shame to hide such curls.”

She arranged it loosely about my shoulders, stepping back to admire her handiwork. “See! It makes those lovely eyes of yours look huge! There’s many a lad in London would be glad to woo a wench with such wonderful dark hair!”

I blushed, making her giggle. Philippa had a liking for young men, and Mistress Mercer teased her about the swaggering young swains who hung about the premises in the hope of a glimpse or a word, but while she chattered and tossed her wayward locks at all of them, Ralph Fowler won her favour. Sometimes, lying in the dark, she told me about him, whispering of their trysts and her hopes of marriage.

“But suppose his parents won’t let him marry you?” I asked, excited by the daring tales she told.

“Pooh!” she said, wrinkling up her nose as if at a bad smell, “they couldn’t stop him. I know how to make him want me so badly, he can’t think of anything else!” Her eyes sparkled as she confided the latest intimacy she’d allowed him, laughing at my ignorance. “I thought country girls knew all about the natural needs of men.” She raised her eyebrows knowingly.

Sometimes Philippa questioned me about my country home. When I spoke of it, I realised how small my village really was. But that didn’t stop me yearning for its green fields and shadowed woodlands. How different did the tiny thatched cottages seem after the teetering city houses with their lofty wooden frames and painted walls, how little the squat-towered church— and yet I craved the earthy smell of the byre, the comforting hiss and fizzle of the forge, the familiar discord of the blacksmith’s clanging music. I understood then how Brother Brian felt about his home across the sea.

“Why did you come to London?” Philippa leaned on her elbow, all curiosity.

“My father died, and my aunt and uncle took me in.” I fidgeted, uncomfortable with the memories this stirred.

“But you don’t live with them now.” She eyed me closely. “Betsy told me they sent you away for conjuring—”

“The fortune-telling got me into trouble,” I answered, incensed by the serving maid’s tittle-tattle. “I wasn’t really to blame. Betsy first suggested it anyway. It was around Twelfth Night and my aunt and uncle had gone out. Judith wanted us to play this game she’d had of Betsy—she said if you threw petals or leaves into a bowl of water, a spirit would show you the letters of your future husband’s name.”

“What happened?” Philippa’s eyes gleamed with excitement.

“I don’t really know. I’d never played it before, but I saw pictures in the water and it frightened them. A face appeared and I screamed. There was a great commotion because my aunt and uncle returned early and I fainted. My uncle was furious and accused me of conjuring spirits.”

“But what made you scream?” Her voice fell to an awed whisper.

“I’d seen that face before in my dreams.”

She waited for more but I didn’t tell her I’d know it anywhere by the piercing brightness of its blue eyes and the sensual curve of its mouth.

During the turbulent events of my eleventh year, however, my new dreams set Philippa complaining.

“She wakes me with nightmares.” She adopted a pained expression. “How can I sleep when she’s always talking about murderers or being chased by monsters with yellow eyes, or setting people on fire? It scares me.”

Harry laughed at her grumbles but Mistress Mercer’s watchful glances put me on edge. I grew clumsy and distracted, spilling flour and dropping loaves, until Big Hal turned me out of the bake-house and sent me on various errands in the city.

Here, the bustling streets and alley-ways buzzed with rumours of new plots to seize the crown. Tired of weak government, the Londoners insulted King Henry openly now, and nick-named his wife “the she-wolf.” Every day I heard more lewd remarks about her. Fat Marion’s bawdy gossip now made sense. People called Queen Margaret’s prince a bastard but they praised the late Duke of York’s eldest son.

“Edward of York’s the handsomest lad in the world,” Philippa said. Her eyes grew dreamy.

“What, handsomer than Ralph Fowler?” Harry feigned shock.

Philippa flounced out of the bake-house into the shop, and we listened to her regaling Mistress Mercer with lurid tales about this golden youth. Big Hal shook his head. His eyes twinkled down at me.

“I daresay you wenches are all in love with this popinjay. But he’s barely eighteen. A king needs more than fine features.”

“Oh Meg told me Nan favoured the apothecary’s lad.” Harry laughed. “But now I hear she’s fond of lads with black hair. I’ve seen her looking—”

It was true I’d told Philippa I’d a fancy for dark-haired men but I never thought she’d betray this confidence to Harry. My cheeks burned with embarrassment and rage. This amused Harry and his father all the more and drove me out of the bake-house too.

Mayb

e the unrest in the city generated my new nightmares. Several times I dreamt of men skulking on a shadowy staircase, carrying a bundle lapped in a bloody counterpane, and the man with black hair and vivid blue eyes dragged me onto a dun-coloured horse and rode off with me into wild, open countryside. One February morning I woke just as the horse stumbled over a rocky ledge dazzled by a huge sun-burst—

Philippa stood by the casement, shivering in her shift. Outside all the bells were ringing. Shouts and hurrying footsteps from the street below shattered the remnants of my dream.

“What is it?” Flinging on a robe, I leaned out to shout down to a skinny lad in the alley-way. “What’s happening?”

“Edward of March, York’s eldest son, has defeated the king and is marching towards London!”

Philippa hugged me. Squealing with excitement, we raced downstairs to celebrate the news.

The Mercers plied their customers with ale that day. Although no one thought the saintly king would really be overthrown, they didn’t want to miss a chance of revelry. Besides, the gossips hailed this victory as a kind of miracle.

Maud Attemore, robust in a bilious green gown with mottled sleeves, had a great crowd about her the following morning when Harry and I walked through the Chepe.

“Three suns shone clear in the heavens on the morning of the battle,” she said. She held up a hand as if to point them out. The listeners stood impressed, goggle-eyed and open-mouthed.

“Three suns indeed!” A jeering voice broke the spell. “What piss! How does a poxy drab know about miracles?”

We turned to confront the beef-faced heckler, a corpulent fellow in a soiled grey doublet bearing a Lancastrian device upon the sleeve.

“Let wenches follow after York’s bastard spawn with the pretty face. He’s not fit to lick Royal Harry’s boots. Didn’t you all swear allegiance to the House of Lancaster? Where’s your loyalty now, eh? Since when did bawds champion kings?”

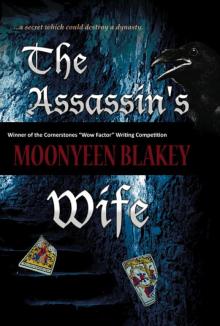

The Assassin's Wife

The Assassin's Wife